Yamantaka, Wrathful Manifestation and Conqueror of Death

This article explores Yamantaka, the wrathful manifestation of Manjushri, revealing his symbolic iconography, the profound spiritual purpose behind his fierce appearance as the "Conqueror of Death," and his central role in Vajrayana Buddhist practice, particularly within the Gelug tradition.

1/18/20264 min read

In the vast and intricate pantheon of Vajrayana Buddhism, there exist deities of profound compassion and serene wisdom, yet equally prominent are those who embody wrath, ferocity, and terrifying power. Among the most formidable of these wrathful manifestations is Yamantaka, often referred to as the "Conqueror of Death."

Far from being a demonic entity, Yamantaka is a highly revered meditational deity, an emanation of the gentle Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Manjushri, whose terrifying appearance serves a singular, profound purpose: to subdue ignorance, attachment, and the ultimate fear of death, thereby leading practitioners to enlightenment. His very existence is a paradox of wisdom appearing as wrath, compassion expressing itself as unyielding power, all aimed at liberating sentient beings from the cycle of suffering.

The origins of Yamantaka are steeped in ancient Buddhist lore and esoteric traditions, particularly within the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, where he holds a supreme position as one of the three principal meditational deities (alongside Chakrasamvara and Guhyasamaja). The narrative of his emergence often begins with the tale of a powerful, sentient being who became so consumed by the fear of death that he transformed into a terrifying buffalo-headed demon, Yama, the Lord of Death, and began to decimate the population of Tibet. Yama, in his destructive rampage, threatened to plunge the world into an endless cycle of suffering and fear.

To counter this existential threat, the compassionate Manjushri, seeing the plight of beings trapped by death's tyranny, manifested in an even more terrifying form, taking on the very essence of death itself to conquer it from within. This fierce manifestation, known as Yamantaka (literally "Slayer of Yama" or "Conqueror of Death"), embodies the ultimate power to overcome not just physical death, but the death of ignorance that binds beings to Samsara. He is the ultimate antidote to the fear of impermanence and the delusion of a permanent self.

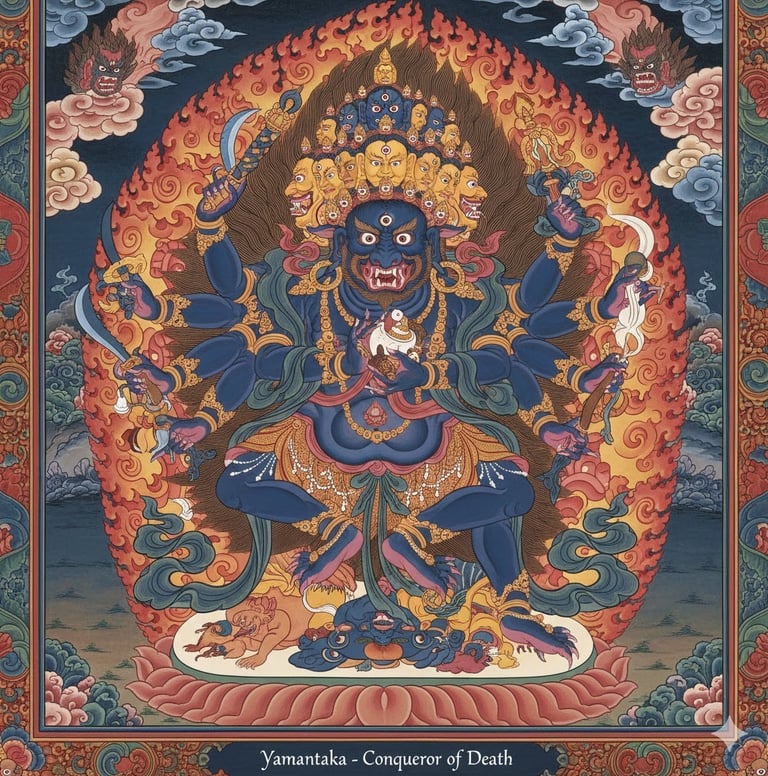

Visually, Yamantaka is arguably one of the most complex and fearsome deities in the Vajrayana tradition. His iconography is rich with symbolic meaning, each element carefully chosen to convey profound aspects of the path to enlightenment. He is typically depicted with multiple heads, arms, and legs, often standing in a ferocious posture, trampling various beings and obstacles. The most common form, particularly in the Gelug tradition, is the Vajrabhairava form, characterized by nine heads, thirty-four arms, and sixteen legs. Each of these features carries specific symbolism: the nine heads represent the nine categories of sentient beings or the nine aspects of the Buddha’s teaching; the thirty-four arms symbolize the thirty-four aspects of the Bodhisattva's practice; and the sixteen legs signify the sixteen voidnesses.

His primary head is often that of a wrathful buffalo, mirroring the very demon he conquered, signifying his mastery over death. Above this buffalo head typically rises the serene head of Manjushri, serving as a constant reminder that this terrifying manifestation is, at its core, pure wisdom and compassion. The fangs, flaming hair, multiple eyes, and garlands of skulls are not meant to inspire fear in the practitioner but to signify the eradication of all delusions, the destruction of ego, and the cutting through of all hindrances to liberation.

The practice of Yamantaka is highly advanced and traditionally requires extensive preparation, including refuge vows, Bodhisattva vows, and Tantric empowerments. It is not a practice undertaken lightly, as it involves engaging directly with powerful energies and confronting one's deepest fears and delusions. Through intricate visualizations, mantra recitation, and meditation, practitioners identify with Yamantaka, transforming their ordinary consciousness into the wisdom of the deity.

This process is not about worshipping an external god, but about realizing one’s own innate potential for enlightenment. By meditating on Yamantaka, one aims to overcome the "inner Yama"—the mental afflictions and karmic imprints that perpetuate suffering and the cycle of rebirth. The wrathful aspect of Yamantaka serves to forcefully cut through these deeply ingrained patterns, offering a direct and potent path to purification and realization.

The flames that often surround him symbolize the blazing wisdom that incinerates ignorance, while the weapons he wields such as the curved knife, skull cup, and ritual staff—are metaphors for the tools used to sever attachments and erroneous views.

The significance of Yamantaka within the Gelug school, founded by Je Tsongkhapa, is particularly profound. Tsongkhapa himself practiced Yamantaka extensively and attributed much of his spiritual realization to this deity. It is said that Yamantaka played a crucial role in Tsongkhapa's own journey, helping him to overcome obstacles and gain deep insights into the nature of reality. Consequently, Yamantaka became a central meditational deity for the Gelug lineage, passed down from teacher to disciple as a secret and potent means to achieve enlightenment.

The Dalai Lamas, as spiritual leaders of the Gelug school, also engage in Yamantaka practice, underscoring its importance and efficacy within the tradition. For practitioners of Yamantaka, the goal is to fully realize the emptiness of all phenomena, including the self, thereby conquering the root cause of suffering and rebirth—ignorance. By meditating on the deity, one gradually dismantles the illusion of a separate, permanent self, which is the ultimate source of fear, attachment, and aversion, including the fear of death itself.

Beyond the individual spiritual journey, Yamantaka's role extends to the protection of the Dharma and its practitioners. He is seen as a powerful protector, capable of warding off negative forces, obstacles, and interferences that might hinder one's practice or the spread of the Buddha's teachings. This protective aspect is crucial for the flourishing of Buddhism, particularly in challenging times. When a practitioner invokes Yamantaka, they are not only seeking personal liberation but also contributing to the collective strength and resilience of the Sangha.

The fierce energy of Yamantaka is believed to purify environments, consecrate sacred spaces, and establish a shield against harmful influences, both mundane and spiritual. His wrath is thus not destructive in a negative sense, but rather a fierce, purifying energy that cuts through all that obstructs genuine spiritual progress and well-being.

In essence, Yamantaka embodies the paradoxical truth that enlightenment can manifest in terrifying forms. His wrath is a skillful means, a potent expression of compassion that shocks the deluded mind into awakening. He is the ultimate conqueror of death, not by granting immortality, but by destroying the ignorance that makes death fearful and rebirth inevitable. Through his profound practice, one learns to confront and transcend the deepest fears, unravel the illusions of self and permanence, and ultimately realize the boundless wisdom and compassion that lie at the core of all being.

Yamantaka stands as a powerful testament to the multifaceted nature of the Buddhist path, demonstrating that liberation can be achieved not only through gentle contemplation but also through the fierce, unyielding power of awakened wrath.

Community

Explore teachings, prayers, and cultural events.

Address

Sera Jey Wisdom Center

Ruko Savoy Blok C1 No.31 & 32,

River Garden Jakarta Garden City,

Cakung Timur, Jakarta Timur 13910,

Indonesia

+62 813 2488 4241

© 2025. All rights reserved.