Between Myth and Mercy: How the Naga Protects the Buddha’s Wisdom

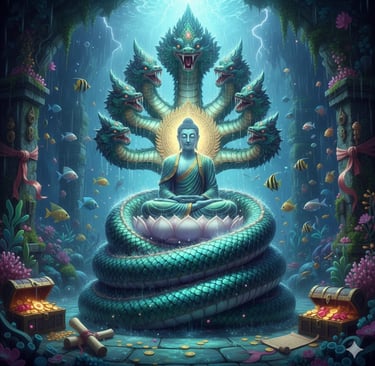

Explore the mystical world of the Nagas, the ancient serpent guardians who bridge the gap between nature and the divine. From shielding the Buddha during his enlightenment to guarding sacred sutras beneath the sea, these powerful spirits embody the dualities of destruction and protection. This article delves into their role as masters of the waters, custodians of hidden wisdom, and timeless sentinels of the Buddhist dharma.

2/8/20265 min read

Deep within the mist-shrouded layers of Buddhist cosmology and the verdant landscapes of South and Southeast Asia, the Naga exists as a bridge between the mundane world and the profound mysteries of the dharma.

These serpent spirits are not merely mythological relics but are vibrant, complex entities that embody the dualities of nature, fearing and fearsome, destructive and protective. In the Buddhist tradition, Nagas are generally depicted as semi-divine beings who inhabit a subterranean or underwater realm called Patala. While they possess the ability to take full human form to interact with the world above, their true essence is that of the great serpent, often represented with multiple heads, hooded like a cobra, and shimmering with scales that reflect the hidden jewels of the earth. Their presence in Buddhist literature serves as a constant reminder that the path to enlightenment is not traveled in isolation from the natural world, but rather in a shared existence with all sentient beings, even those whose forms are alien to our own.

The origins of the Naga in Buddhism are inextricably linked to the pre-Buddhist animistic traditions of India, where snakes were revered as the masters of the soil and the bringers of rain. When Buddhism began to flourish, it did not discard these local spirits but instead integrated them into its spiritual tapestry, casting them as converted protectors of the Buddha’s teachings. This transition from wild, unpredictable spirits to disciplined guardians is perhaps most famously illustrated in the story of Mucalinda. According to the Vinaya Pitaka, during the sixth week following the Buddha’s enlightenment, a massive storm broke out while the Awakened One sat in deep meditation. Mucalinda, the king of the Nagas, emerged from his subterranean abode and coiled his body seven times around the Buddha, extending his great hood to shield him from the torrential rain and freezing winds. This iconic imagery, which has been immortalized in countless statues across Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, symbolizes the ultimate reconciliation between the raw power of nature and the stillness of the enlightened mind.

Water is the primary domain of the Naga, and through this association, they are viewed as the absolute masters of the hydrological cycle. They reside in the depths of lakes, rivers, and the vast oceans, but they are also believed to dwell in the clouds, where they control the falling of rain. For agricultural societies throughout history, the favor of the Naga was synonymous with survival; a content Naga brought gentle rains and bountiful harvests, while an offended Naga could trigger devastating droughts or catastrophic floods. This connection to water also bestows upon them a role as the guardians of "treasures," a term that carries both literal and metaphorical weight in Buddhist thought. Literally, they are the keepers of gold, pearls, and precious gems hidden beneath the earth and sea. Metaphorically, they are the custodians of hidden knowledge and sacred texts that the human world is not yet ready to receive.

One of the most significant examples of the Naga as a guardian of wisdom involves the philosopher-saint Nagarjuna, the founder of the Madhyamaka school of Mahayana Buddhism. Tradition holds that the Prajnaparamita Sutras, or the "Perfection of Wisdom" texts, were entrusted to the Nagas by the Buddha because the people of his time lacked the intellectual and spiritual capacity to grasp their profound emptiness. Centuries later, Nagarjuna traveled to the underwater kingdom of the Nagas, where he was deemed worthy of these teachings. He returned to the human realm with the texts, effectively sparking a revolution in Buddhist philosophy. This legend positions the Naga not just as a magical creature, but as a crucial link in the transmission of the dharma, acting as a celestial "safety deposit box" for truths that transcend time and cultural limitations.

The relationship between Nagas and the monastic community, or Sangha, is marked by a poignant sense of longing and spiritual limitation. There is a well-known story in the Buddhist canon about a Naga who desired so deeply to follow the Buddha’s path that he transformed himself into a human and sought ordination as a monk. For a time, he lived undetected among the brethren, but one night, while he was in a deep sleep, his human disguise slipped away, and his true serpentine form was revealed. When the Buddha was informed, he explained that only human beings possess the specific karmic "middle ground" necessary to achieve full enlightenment and monastic ordination. The Naga was heartbroken, and the Buddha, moved by his devotion, decreed that while the serpent could not be a monk, all candidates for ordination would henceforth be called "Naga" during the ceremony as a tribute to his spirit. This tradition persists to this day in several Buddhist lineages, where the term "Naga" serves as a title for a novice about to undergo the transition into the monastic life.

In the physical world, the presence of the Naga is often signaled by specific geographic features and sacred sites. In the Mekong River, for instance, the phenomenon of the "Naga Fireballs"—glowing orbs that rise from the water into the night sky—is celebrated annually by thousands of pilgrims who believe the serpents are honoring the end of the Buddhist Lent. In temples across Southeast Asia, the Naga is a dominant architectural feature, with their long, sinuous bodies forming the balustrades of staircases and their heads crowning the gables of roofs. These "Naga bridges" symbolize the transition from the profane world of the senses to the sacred space of the temple, mirroring the creature's role as a threshold guardian who facilitates the movement between different planes of existence. The intricate carvings of Nagas are often found flanking the entrances to caves or surrounding the base of stupas, serving as a warning to the impure and a welcome to the devout.

However, the nature of the Naga is not exclusively benevolent. They are portrayed as temperamental beings, prone to anger and capable of exhaling poisonous breath or casting powerful illusions if their habitats are disturbed or if humans act with greed and disrespect toward the environment. This aspect of Naga lore serves as an early form of ecological ethics; it teaches that the resources of the earth—the water we drink and the minerals we mine—are not ours to take without consequence. They belong to a wider ecosystem inhabited by spirits who demand respect. To pollute a stream or desecrate a mountain is to invite the "Naga’s curse," which often manifests as skin diseases or misfortune. Thus, the Naga acts as a spiritual enforcement mechanism for the preservation of the natural world, reminding humanity that our dominion over the earth is an illusion and that we share our home with forces far more ancient and powerful than ourselves.

The complexity of the Naga also extends to their place in the "Six Realms of Existence" within Buddhist rebirth theory. Though they possess great wealth and magical powers, they are technically classified as part of the animal realm or as a class of Asuras (demigods), which means they are still subject to the cycle of suffering and rebirth. They are said to suffer from "five inevitable distresses," including the pain of their scales being infested by heat and parasites, and the constant fear of their natural predator, the Garuda—a giant, solar bird-like deity. This vulnerability humanizes the Naga, making them relatable figures within the Buddhist cosmos. They, too, are seekers of liberation; they, too, are bound by their karma. Their devotion to the Buddha is rooted in a desire to eventually transcend their serpentine forms and attain the human birth necessary for final Nirvana.

Ultimately, the Naga represents the hidden depths of the mind and the latent potential of the earth. They are the keepers of the cool, dark places where wisdom germinates before it reaches the light of day. In the context of modern Buddhism, the symbolism of the Naga remains as relevant as ever, reminding practitioners that the dharma is not just found in books or silent meditation halls, but in the living, breathing world around us. By honoring the Naga, the Buddhist tradition honors the interconnectedness of all life forms, recognizing that even the humblest serpent or the most hidden spring of water is a vessel for the sacred. The Naga stands as a timeless sentinel at the intersection of myth and reality, ensuring that the treasures of the water and the treasures of the law remain protected for those who have the eyes to see and the heart to understand.

Community

Explore teachings, prayers, and cultural events.

Address

Sera Jey Wisdom Center

Ruko Savoy Blok C1 No.31 & 32,

River Garden Jakarta Garden City,

Cakung Timur, Jakarta Timur 13910,

Indonesia

+62 813 2488 4241

© 2025. All rights reserved.